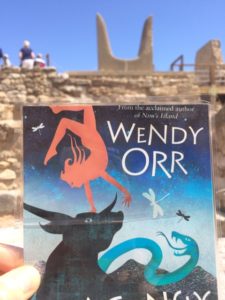

One of my favourite writers is Wendy Orr who, like me, writes for both adults and children. Her latest book, Dragonfly Song, is likely to appeal to both, being set in Minoan Crete. The main character is a bull-dancer…

That’s so far away from the era of my own books that I was fascinated by the kind of research Wendy has had to do for the book – I know it’s taken her a very long time to get to the point where she felt she could write it. Very kindly, she’s written about that process for this blog.

I asked her: What are the pleasures and pitfalls of researching such a long-ago era?

Wendy:

Although this is a very different era to the one you’ve specialised in, there’s the same joy of discovering not just new facts, but new questions – and of course questions are always the start of a story. I think the main difference is that the farther back you go, the fewer answers there are – at least, fewer firm, factual answers. That makes fiction both easier, and harder.

Dragonfly Song is set in the Minoan Bronze Age world, a decade or so before its final destruction in 1450 BCE. This was a fascinating civilisation, extraordinarily advanced – a favourite example is that they had flushing toilets – that left no written records of its history or culture. The only writing that has been found and deciphered is stocklists or tax accounts. Though I loved knowing that someone had a cow named Blackie! Funny little details like that instantly bring even a list of livestock to life.

But, with nothing to base theories on except material remains, interpretations vary widely. I heard one archaeologist say that her impression of the Minoans was that they were all very beautiful. Hmm. So is everyone from the 20th and 21st centuries, if our impression is based purely on red carpet photos. I’m equally doubtful that goddess figurines mean that women held all the power.

Still, I have to confess that I first became fascinated with the Minoans after a dream about a white-robed priestess leading a torchlight procession up a mountain. I don’t believe there was any sort of message or accuracy in the dream, but it was the impetus to my reading everything that interlibrary loans could give me on Bronze Age mythology, and the Minoans and Mycenaeans. This reading itself was back in the distant pre-internet period of history. Of course I wrote about it too, a melodramatic romance that was very nearly, but luckily not, published.

When I returned to the subject twenty-five years later, there was not only a huge amount of new material and revised theories – through the magic of Google, I had access to much of it. An overwhelming amount, much more than I needed. And so, as with any research for any fiction, the difficulty became knowing when to stop. It’s easy to become obsessional and decide that you can’t finish the book until you know exactly how goats were herded in the 15thC BCE. Or exactly how the bulls got from wherever they were to the bull-game court in Knossos. Or which court it was.

The only thing to do is to draw a deep breath and remember that I’m writing fiction. If no one knows the answer for sure, all I can do is to choose the theory that makes sense to me, and if there’s no theory, then work out my own as logically as I can. And sometimes, when I’ve done all that, I still have to choose to change it for the sake of simplicity and story line. So although the Minoans sometimes saluted with a fist to the forehead, and sometimes with a hand on the heart, I chose the hand on the heart. It worked better for my story, and is easier to picture. Did that stop me feeling anxious when I visited the Archaeological Museum and saw the fist-to-forehead statuettes for myself? Of course not. But will readers be happier with one clear thing to picture in such a different world to their own? I hope so. Because in the end, the research is only the start of the story. It builds the world, but characters are formed with our hearts.